I heard this week that Prof. Richard Bauckham (St Andrews and Cambridge) likes and is convinced by the main points of my argument for a carefully worked out numerical structure in the reworked Shema that Paul cites in 1 Cor 8:6.

(The reworked Shema in 1 Cor 8:6 has two parts, each composed of thirteen words in a way that says that together, the one God the Father and the one Lord Jesus Christ constitute the divine identity of the God who has revealed himself to Israel. The God of the Hebrew Bible is Yhwh, whose name carries the numerical value of twenty-six by the rules of Hebrew gematria. Thus the number of words in the two parts of the confession in 1 Cor 8:6 add up to the value of the name of the one God. There is more to the numerical structure than that, but this is the essence of my argument (which I present in chapter of my Jesus Monotheism, Volume 1).

This is a great encouragement. Bauckham has been a pioneer in the application of numerical criticism to the New Testament and, over many years, he has worked closely on New Testament Christology and the Jewish material related to it.

He has also suggested to me a minor modification of my argument, which I think is sensible and which prompts to makes some further suggestions as to the significance of 1 Cor 8:6 for Pauline theology.

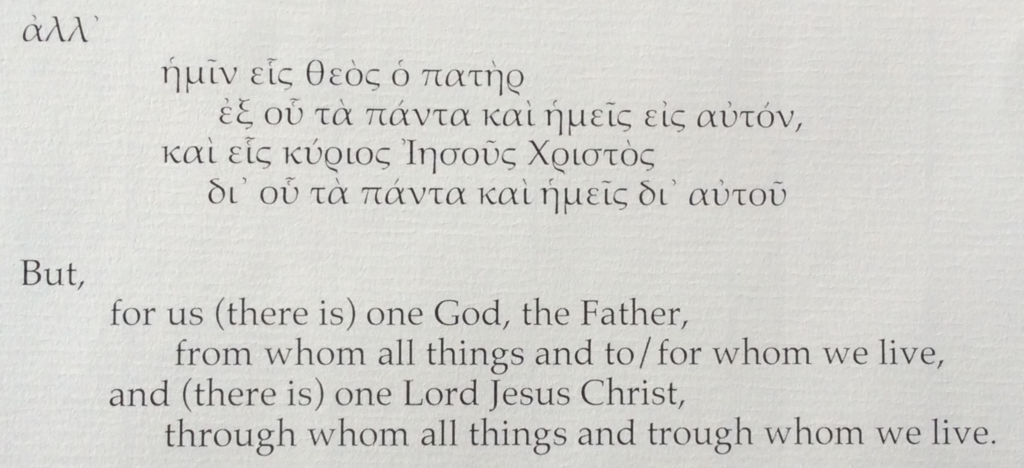

I have argued that in 1 Cor 8:6 Paul is quoting from a well-known confession that is based on the first line of the daily Jewish prayer known as the Shema (= Deut 6:4), in which case the first word of 1 Cor 8:6 (“But,” ἀλλά in Greek) is not part of the confession known to the Corinthians. Paul’s “But” just introduces the confession. So the verse can be laid out like this:

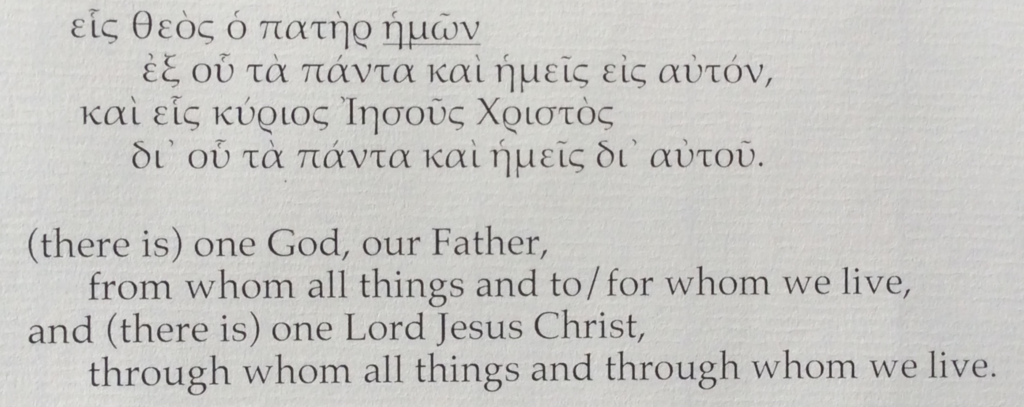

Bauckham points out that the word ἡμῖν (“for us”) is probably used to ensure that the confession fits the literary context of the letter to the Corinthians and more likely the confession itself had the genitive plural form of the pronoun, ἡμῶν (“our”), with Father:

I can see three reasons why this is likely the actual form of the confession. And those considerations lead to a rather important conclusion.

(1) The word ἡμῶν (“our”) after ὁ πατὴρ (“the Father”) makes for a neater balance between the first and third lines:

εἷς θεὸς ὁ πατὴρ ἡμῶν

καὶ εἷς κύριος Ἰησοῦς Χριστός

(2) The word ἡμῶν (“our”) makes for a clearer relationship to the first line of the Shema which everyone agrees is the OT base text for Paul’s words:

Ἄκουε, Ισραηλ· κύριος ὁ θεὸς ἡμῶν κύριος εἷς ἐστιν·

Hear, Israel! The Lord our God, the Lord is one.

(3) If the confession opened with the words εἷς θεὸς ὁ πατὴρ ἡμῶν then it must have reflected traditional, conventional, early Christian language for God.

According to Matthew, Jesus taught his disciples that when they pray they should pray this way: “Our Father (Πάτερ ἡμῶν) in heaven …”

Paul repeatedly uses the words θεὸς πατὴρ ἡμῶν “God our Father,” especially in blessings and prayer wishes. The expression (or its variant “θεὸς ὁ πατὴρ ἡμῶν”) appears eleven times in the Pauline letters (if we include manuscripts with the longer text at 2 Thess 1:2): Rom 1:7; 1 Cor 1:3; 2 Cor 1:2; Gal 1:3; Eph 1:2; Phil 1:2; Col 1:2; 2 Thess 1:1, 2; 2:16; Phlm 3. Similar phrases appear also in Gal 1:4; Phil 4:20; 1 Thess 1:3; 3:11, 13.

All this is important because if the confession has two parts that begin εἷς θεὸς ὁ πατὴρ ἡμῶν and εἷς κύριος Ἰησοῦς Χριστός respectively, then Paul probably alludes to the confession multiple times in his letters. Consider these Pauline verses:

1 Cor 1:3 Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ (ἀπὸ θεοῦ πατρὸς ἡμῶν καὶ κυρίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ).

2 Cor 1:2 Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ (ἀπὸ θεοῦ πατρὸς ἡμῶν καὶ κυρίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ).

Gal 1:3 Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ (ἀπὸ θεοῦ πατρὸς ἡμῶν καὶ κυρίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ).

Eph 1:2 Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ (ἀπὸ θεοῦ πατρὸς ἡμῶν καὶ κυρίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ).

Phil 1:2 Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ (ἀπὸ θεοῦ πατρὸς ἡμῶν καὶ κυρίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ).

See the similar coupling of “God our Father” and “the Lord Jesus Christ” in Col 1:2; 1 Thess 1:3; 3:11; 2 Thess 1:1, 2; 2:16; 1 Tim 1:2; Phlm 3; 1 Pet 1:3.

Every time Paul speaks of “God our Father” and “the Lord Jesus Christ” in the same breath he probably has in mind the redefined divine identity of the one God spelt out in 1 Cor 8:6. Paul thinks, prays and worships according to a grammar moulded by the conviction that the one God of biblical revelation is now two.